ISIS' high-profile hostages

ISIS Hostages

(CNN)In its short, bloody existence, ISIS has taken dozens of international hostages.

Often its has sought ransoms for them to swell its coffers, and some governments have reportedly handed over hefty sums of cash.

In

other cases, where money isn't forthcoming, the Islamic militant group

has publicized its barbaric killings of the hostages, apparently in an

effort to score propaganda points with its extremist followers.

The

number of foreign captives killed by ISIS is dwarfed by the masses of

Iraqis and Syrians slaughtered under the militants' murderous rule over

parts of the region.

But the fates of

some of ISIS' most high-profile hostages, outlined below, have brought

home to the West the brutality of the militant group.

James Foley

The

first American hostage whose slaying ISIS publicized, James Foley was a

freelance journalist from Rochester, New Hampshire, who was abducted

during a reporting trip in northern Syria in November 2012. He had a

"bold commitment to bearing witness of the suffering in conflict zones,"

according to his family. Foley had previously been held captive in

Libya by forces loyal to the former dictator Moammar Gadhafi.

ISIS

at one point demanded a ransom of 100 million euros ($113 million, at

current exchange rates) for Foley's release, according to GlobalPost,

one of the news organizations for which he worked.

U.S. special forces failed to find Foley, 40, and other American hostages during an attempted rescue operation in July.

A video of his beheading was posted online on August 19.

In his last letter,

conveyed to his family by a former fellow hostage who memorized it just

before his release, Foley talked about memories, like a long bike ride

with his mom, that took him "away from this prison."

And

he underscored how prayer had helped him during his ordeal: "I feel you

all especially when I pray. I pray for you to stay strong and to

believe. I really feel I can touch you even in this darkness when I

pray."

Steven Sotloff

Freelance writing for publications like Time and The Christian Science Monitor took Steven Sotloff to the Middle East.

"I know reporting on an international level is what he always wanted to do," recalled one of his college friends.

Sotloff,

a Miami Dolphins fan from South Florida, visited a range of countries

including Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and eventually Syria. Shortly

after crossing into the war-torn nation in August 2013, Sotloff and his

guide were kidnapped by gunmen who jumped out of cars.

Sotloff's family has suggested

that other rebels received tens of thousands of dollars for tipping off

ISIS that he had entered Syria. The family refrained from public

comment during his captivity, but broke their silence after ISIS

released a video of his beheading on September 2, 2014.

Sotloff, 31, was "no war junkie," they said.

"He

merely wanted to give voice to those who had none," they explained. He

studied Arabic, enjoyed watching South Park and would chat to his dad on

Skype about his golf game. "Steve had a gentle soul that this world

will be without," his family said, "but his spirit will endure in our

hearts."

David Haines

It

was in the Balkans that David Haines, who grew up in Scotland, started

to realize that he wanted to become a humanitarian aid worker. At the

time, he was an aircraft engineer for Britain's Royal Air Force serving

under the United Nations.

He found

himself "helping people in real need," according to his brother, Mike.

After he left the air force, he spent more than a decade helping the

victims of conflicts in different parts of the world.

"David was most alive and enthusiastic in his humanitarian roles," his brother said.

His

work as a logistics and security manager for the Paris-based relief

group ACTED took him to a refugee camp in Syria, near the border with

Turkey.

Haines was abducted near the

camp in March 2013. His family said they had repeatedly tried to make

contact with his captors but never heard back. ISIS threatened to kill

him in the video of Sotloff's slaying. And on September 13, 2014, the

militants posted a video showing the beheading of Haines, a 44-year-old

father of two daughters.

"His joy and

anticipation for the work he went to do in Syria is for myself and

family the most important element of this whole sad affair," his brother

said. "He was and is loved by all his family and will be missed

terribly."

Alan Henning

A

taxi driver from northwest England, Alan Henning traveled with a group

of Muslim colleagues and friends to Syria in December 2013 to deliver

food and water to people affected by the civil war. They nicknamed him

"Gadget" because he loved to fix things. It was his fourth trip to Syria

with an aid convoy, and he was the only non-Muslim in the group.

"It's

all worthwhile when you see what is needed actually gets where it needs

to go," he said in a video recorded the day before he was kidnapped by

masked gunmen.

After ISIS threatened to kill Henning, 47, in September 2014, his wife publicly pleaded with them to spare him, describing the father of two as a "peaceful, selfless man."

"I

cannot see how it could assist any state's cause to allow the world to

see a man like Alan dying," she said. But ISIS ignored her calls,

releasing a video showing his beheading on October 3. His wife

reportedly said that family and friends were "numb with grief" after

receiving "the news we hoped we would never hear."

Peter Kassig

After

spending time in the Middle East as a U.S. Army Ranger stationed in

Iraq, Peter Kassig said he felt compelled to go back to the region to

help people caught up in the Syrian conflict. He trained as an emergency

medical technician and went to offer his services in Lebanon, where

many Syrian refugees end up.

"The way I saw it, I didn't have a choice," he told CNN

in 2012. "This is what I was put here to do. I guess I am just a

hopeless romantic, and I am an idealist, and I believe in hopeless

causes."

Kassig eventually founded

Special Emergency Response and Assistance, an aid organization, and

moved its base of operations to a Turkish city near the Syrian border in

the summer of 2013. He was on his way to Deir Ezzor in eastern Syria

for work when he was detained on October 1, 2013. His family said that

they, along with friends and colleagues, worked "tirelessly and quietly"

to try to secure his release.

He

converted to Islam during his captivity, changing his name to

Abdul-Rahman Kassig, although the journey toward the faith started

before his abduction, his family said. ISIS published a video showing

his beheading on November 16, 2014.

Haruna Yukawa

A

series of heavy setbacks in life befell Haruna Yukawa before he decided

to travel to the Middle East with dreams of running his own private

security company. Over the previous decade, he had attempted suicide,

lost his wife to cancer, and then lost his home and business. The events

appeared to take a psychological toll.

On

a blog, Yukawa once wrote, "I look normal outside, but inside I'm

mentally ill." He came across as a lost soul, but he appeared to find

renewed purpose in Syria.

"He seems to have felt satisfaction being there and living together with the locals," one of his friends told CNN.

But

Yukawa, 42, was abducted in August 2014 and ended up in the hands of

ISIS. His plight gained wider attention last month when ISIS posted a

video threatening to kill him and another Japanese hostage unless Tokyo

paid a $200 million ransom. Days later, on January 24, they released a

video containing an image of Yukawa's decapitated body.

"I

have been praying such a thing would not happen but, unfortunately, it

has finally come to pass and my heart aches," his father, Shoichi, said.

Kenji Goto

The other Japanese hostage, Kenji Goto,

was a veteran journalist who had been reporting from conflict zones for

years. He said he wanted to tell the stories of people suffering in war

zones, especially children.

Goto, 47,

met and befriended Yukawa in Syria, apparently helping show his less

experienced compatriot how to get by in a risky environment. After

Yukawa's capture, Goto decided to head into ISIS-controlled territory to

try to rescue his friend, leaving his wife and three daughters in

Japan, the youngest of them only three weeks old. He reportedly told a

Syrian colleague that he thought he would be OK because he wasn't

American or British.

But ISIS

apparently didn't see it that way, adding him to its collection of

foreign hostages. After announcing the killing of Yukawa, ISIS said they

would swap Goto for an Iraqi terrorist on death row in Jordan. But no

deal was reached and on January 31, ISIS released a video showing Goto's

beheaded body.

"Kenji always has been

a kind person, ever since he was little," his mother, Junko Ishido,

said. "He was always saying, 'I want to save the lives of children in

war zones.'"

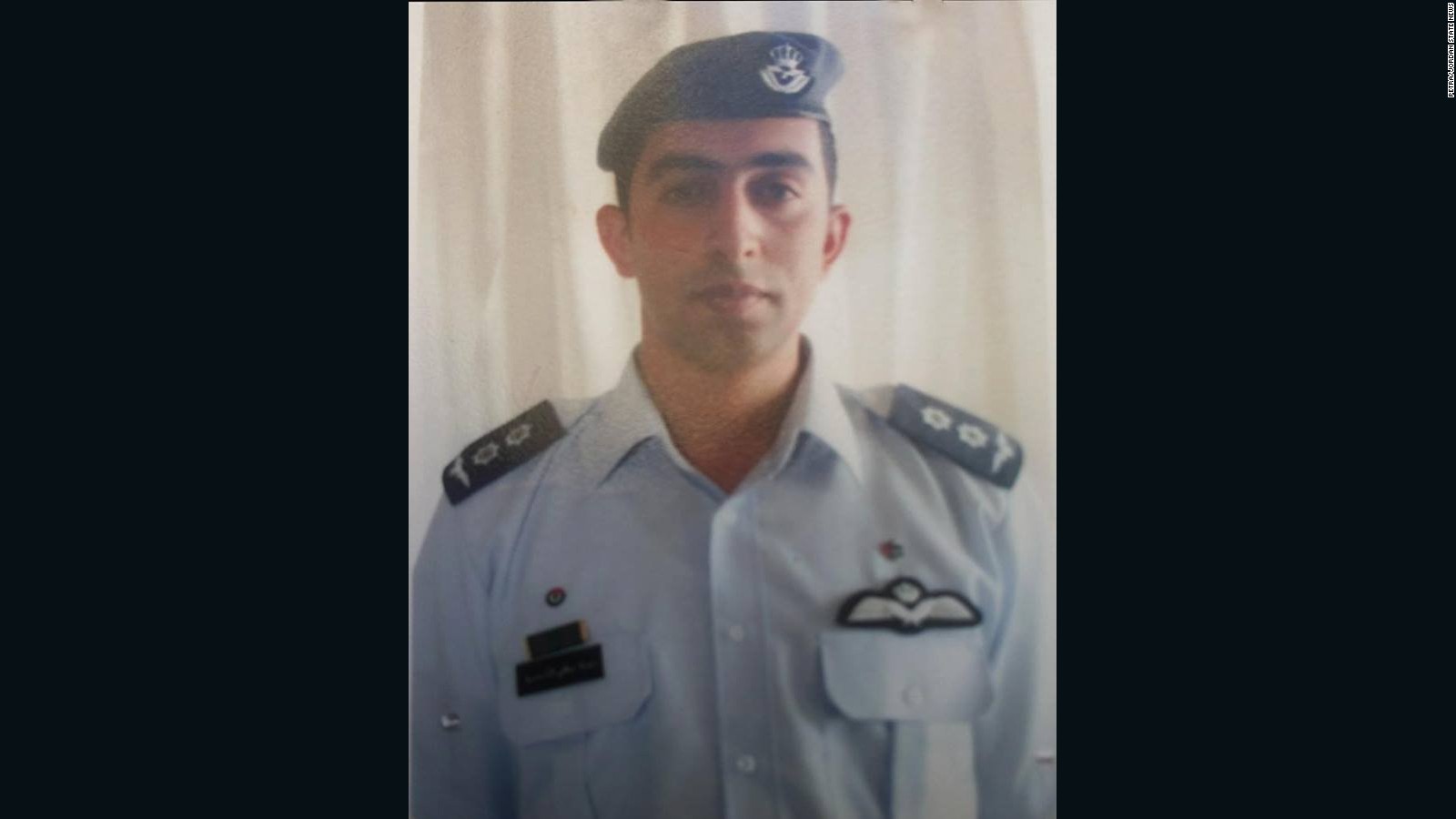

Lt. Moath al-Kasasbeh

After his F-16 fighter jet crashed over Syria in December, Royal Jordanian Air Force pilot Lt. Moath al-Kasasbeh

was taken prisoner by ISIS. He was the first member of the coalition of

air forces carrying out bombing raids on ISIS targets in Syria and Iraq

to fall into the hands of the militants.

Al-Kasasbeh,

27, was a devout Muslim who memorized the Quran and hailed from a large

family and prominent tribe noted for its loyalty to the monarchy. One

of eight children, he was "a very modest and religious person,"

according to his father, Safi al-Kasasbeh. He had gotten married just a

few months before his plane crashed in Syria.

The

pilot's fate after his capture was unknown until ISIS brought him into

the equation of the prisoner swap of Goto for the Iraqi terrorist. But

they never explicitly offered to release him and didn't provide Jordan

with a proof-of-life for him.

On

February 3, ISIS posted a video and images showing the killing of

al-Kasasbeh in which he was burned alive in a cage. Jordanian officials

said they believed he had been killed weeks earlier, on January 3.

"He always wanted to be a pilot," his cousin, Layla al-Kasasbeh, said after the news of his death. "He was a really smart guy, and everyone loved him."

Kayla Mueller

From her teenage years onward, Kayla Mueller devoted herself to helping those less fortunate than her.

In

high school and at college, she campaigned against international

atrocities. After graduating from college in 2009, the Arizona native

traveled to northern India, the Palestinian territories and Israel to

assist humanitarian groups, her family said. She then went to Syria to

help people whose lives had been torn apart by war, especially children.

"Syrians are dying by the thousands

and they're fighting just to talk about the rights we have," the

humanitarian worker told The Daily Courier, her hometown paper in 2013.

She

was kidnapped in August 2013 after leaving a Doctors Without Borders

hospital in the city of Aleppo, her family said. They heard nothing from

her captors until 10 months later, when ISIS got in touch with a ransom

demand of nearly $7 million. Her parents said the militants told them

they would treat her as their guest.

But

on February 6, ISIS claimed Mueller had been killed in a building that

was hit during a Jordanian airstrike on Raqqa. Her parents initially held out hope that she might still be alive, but they announced Tuesday that they had received confirmation she had lost her life.

"Kayla

was a compassionate and devoted humanitarian," the family said. "She

dedicated the whole of her young life to helping those in need of

freedom, justice and peace."

John Cantlie

A

British photojournalist who has also written articles for newspapers,

John Cantlie was captured in northern Syria at the same time as James

Foley. His LinkedIn profile says he has 20 years of experience and

specializes in working in hostile environments, including Afghanistan,

Somalia and Libya.

"I love stories of

ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances," he wrote in an online

portfolio describing his work. He was previously abducted in Syria with a

Dutch journalist in July 2012. Both were shot when they tried to escape

through a hole in their tent. Several days later, they were rescued by

Free Syrian Army rebels.

ISIS appears

to have used Cantlie differently to its other Western hostages, making

him perform as a journalist telling ISIS' side of the story.

"You're

thinking, 'He's only doing this because he's a prisoner. He's got a gun

at his head, and he's being forced to do this.' Right? Well, it's true.

I am a prisoner. That I cannot deny," Cantlie said in the first video

in September 2014. "But seeing as I've been abandoned by my government

and my fate now lies in the hands of the Islamic State, I have nothing

to lose."

Cantlie's most recent appearance in ISIS propaganda came in a video released this week in which he acts as though he's reporting on the situation in Aleppo. He says, though, that this is the "last in this series."

Comments

Post a Comment